Red flags in research as a means to overcome group think

How independent tests can help to overcome group think so as to enhance fraud detection.

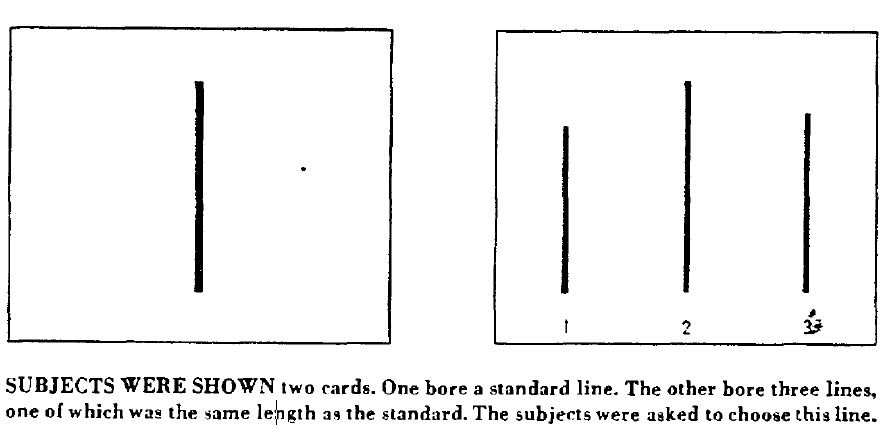

In his classic experiment in 1955, Solomon Asch showed that as soon as one person paints an incorrect picture, this picture is confirmed by a non-trivial number of others. In his research Asch shows four lines: the test line and lines 1, 2 and 3. Participants in his research must indicate which of the lines 1, 2 or 3 is of the same length as the test line. Of the individual participants, 99% give the correct answer 2. But if the first in the row of participants (Asch’s assistant) points to the evidently shorter line 1, 3 percent follows Asch’s assistant. This percentage rises to 33% if the first three participants select 1. This phenomenon has been coined conformity bias or group think where people are willing to ignore reality and give an incorrect answer in order to conform to the rest of the group. I reproduce the original card Asch used in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Original instrument in Opinions and Social Pressure.

The original instrument can be found at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24943779.pdf

Unfortunately we tend to believe cheaters in a similar fashion. As long as leading individuals applaud the work of a cheater the cheater is unlikely to be revealed as a fraud. Diederik Stapel was applauded by the academic society as the most prolific researcher in psychology until he was caught by a group of Phd students. When the president of Tilburg University presented the inexorable facts to Stapel he defended himself with the words that his methods were simply unorthodox. It now appears that the worldwide renown academic Francesca Gino has been tampering with the data so that she would get the results she was looking for. In her case co- author Max Bazerman called the evidence presented to him by the University “compelling.”

Both researchers were acclaimed scholars by both academics as well as practitioners. We -including university executives and university regulators- love academics who publish at the top podium and keep hitting the headlines of the News Papers. Academics who cast doubt on the importance of the work and/or its credibility are ridiculed. So, hardly any individual dares to say that line 2 is equally long as the test line; group think at work!

Couldn’t we have and should we have known better? The answer is yes to both questions, but what mechanism could we use to do away with the group think coined by Solomon Asch? I propose to ask a simple question that should trigger the question whether an audit is warranted or not.

One question that might trigger such an audit is: How many top publications can one individual get published to claim that (s)he paid serious attention to the paper and how did the data come about? For instance, in economics scholars already reach the league of stardom if they publish about 2 papers in a top 5 journal a year. Let’s set the average number of top publications at 2 and the standard deviation as well. If the academic then was able to produce 6 publications, it would be considered a fantastic result.

Too fantastic?

The good news is that academics exposed the cases of both Stapel and Gino as fraudulent. The publication rates of both Stapel and Gino extend far beyond the measure of two papers a year. The chance that someone passes the mark of 6 times the standard deviation is small. Be careful here, it is not impossible for someone to get a lot of publications. For example, we see that the mathematician Paul Erdős published more than 1500 papers with others during his lifetime. The field of expertise also determines production. Some academics run a business like Rembrandt van Rijn with many apprentices, but it does make a heck of a difference whether Rembrandt’s did or did not work on the painting himself. It is the same with academic work.

On twitter Sa-kiera Hudson of Berkeley’s Haas School of Business stated that she was “supremely sceptical of the folks who decide to police what is real vs fake science and who is doing it ‘well’”. The answer to that question is simple: the executive board of the university should decide who to police.

Now I do not have the exact standard deviation or the average number of top publications representing the psychology discipline, but it would be good to make such a calculation for each discipline in order to be able to ask our self: Do I see a red flag or not? This approach should help universities to look into the question whether an audit about contribution and potential fraud is called for and indeed establish with more certainty that we do have an academic star in our midst or a pretender. An independent test should help us overcome group think.

After all Super(wo)man only exists in comics.

Asch, Solomon E. “Opinions and Social Pressure.” Scientific American, vol. 193, no. 5, 1955, pp. 31–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24943779.